With the recent high-profile ransomware attack on Colonial Pipeline Co., more companies than ever before have started to think about the potentially devastating consequences of cyber attacks and how to best protect themselves from them. Cyber attacks that affect critical infrastructure can not only paralyze the targeted organization, but often have downstream impacts on the health and safety of citizens, economic stability, and supply chains to name a few.

Cybersecurity frameworks are often at the starting line as organizations start or revamp their cybersecurity programs. But, navigating the cybersecurity framework landscape can be challenging. Where do you start? What framework is the best choice for my organization’s objectives? Will I need to use multiple frameworks? How difficult will it be to implement these frameworks?

I recently spoke with my colleague David White, the co-founder and President of Axio, for a webinar on cybersecurity frameworks, and we explored these questions and much more. Here are some of the biggest takeaways from the to help you think about frameworks in the most productive way.

Understanding the Three Cybersecurity Standards Categories (Your Menu)

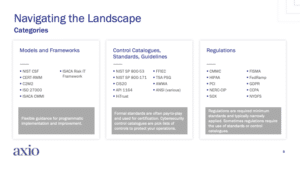

When it comes to understanding what separates frameworks from each other, it’s important to put them into three somewhat distinct categories: 1) models and frameworks, 2) control catalogs, standards, and guidelines, and 3) regulations. Importantly, all of these categories are sometimes generically referred to as “frameworks,” but for the purposes of this discussion, let’s use these categories to explore the similarities and differences. As you evaluate what might work best for your organization’s unique context, these categories will help your decision-making.

Models and Frameworks

The category of models and frameworks describes bodies of work that provide flexible guidance for cybersecurity program implementation and improvement. Some of the most foundational and vital frameworks are included in this bucket.

This category includes models and frameworks such as the National Institute of Standards and Technology’s Cybersecurity Framework (NIST CSF), CERT Resilience Management Model (CERT RMM), Cybersecurity Capability Maturity Model (C2M2), and ISO/IEC 27000. Of these models and frameworks NIST CSF has become popular for program development and benchmarking and played a transformative role in modern cybersecurity practices. And there is much cross-pollination in this category as CERT-RMM is a foundational basis for C2MA and influenced the development of NIST CSF. In a way, the symbiotic relationship between entries in this category has made all models stronger and more comprehensive.

Organizations typically select from this category if they are starting from scratch or have an internal imperative to improve their existing security program. Additionally, as part of organizational oversight of their program, they may use these models for benchmarking because they are commonly known and used in their industry or sector. Boards of Directors often prefer to understand cybersecurity progress in terms of how well their organization is performing relative to peers—and the models and frameworks in this category can support that objective since they are typically in broad use.

Control Catalogues, Standards, and Guidelines

Control catalogs, standards, and guidelines are sometimes a bridge between the other two categories. Control catalogs typically represent lists of controls that can be used to institutionalize your security program’s objectives. Formalized standards are typically pay-to-play and focus on achieving a level of performance that implies competency in the form of “certification.”.

The most popular control catalogs are reflected in nearly all other models, frameworks, and regulations. These include NIST 800-53, NIST 800-171, NIST 800-30, and CIS20 to name a few. Of these, NIST 800-53 remains the gold standard, elements of which are not only reflected in other models and frameworks, but may be specifically prescribed as you will see in the regulations discussion. First released in 2005 and updated frequently, (most recently in September 2020)it was developed with a focus on use in a government context, but enjoys broad use both directly and indirectly across industry. NIST 800-53 is extensive and can take considerable effort to implement. As a result, some organizations opt for using the Center for Internet Security Top 20 controls (CIS20). The CIS20 are a more concise set of practices aimed specifically at defending against cyber-attacks that provide broad coverage like NIST 800-30, but may be more industry-friendly in implementation effort

If you are faced with using a control catalog as your main program framework it is likely you’re in a government organization or the controls are prescribed as a way to implement and institutionalize your choice of model or framework. Thus, by using a control catalog, you might find yourself confronted with operating in a multi-model environment since control catalogs typify the “how” to a model or framework’s “what.”

Regulatory Frameworks

Regulatory frameworks typically emerge as a way to encourage and enforce specific behaviors and outcomes. They often define required minimum standards and may be narrowly scoped to achieve a specific objective; as a result, they may not be comprehensive and often require use of additional frameworks or control catalogs to address a range of program functions. Choosing a regulatory framework for cybersecurity program development or improvement is not usually optional—they are typically forced on organizations as a result of their industry, participation in a critical infrastructure sector, interaction with government or military, or compliance with a set of rules, regulations, or laws.

Some of the more common regulatory frameworks in use include the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPPA), Federal Information Security Modernization Act (FISMA), Federal Risk and Authorization Management Program (FedRAMP), California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA), and New York Department of Financial Services (NYDFS) cybersecurity regulation. Additionally, companies that want to do business in Europe must comply with all the rules laid out by the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). Many of these regulatory frameworks are descriptive in nature but implemented via the use of common control catalogs such as NIST 800-53. The use of a specific control catalog may be prescribed, so while there may be some ability to interpret the regulations required in the framework, the practices implemented to meet the requirements might be prescriptive.

Some Frameworks Straddle The Line Between Categories

The Cybersecurity Maturity Model Certification (CMMC) framework is emerging as a requirement for organizations that want to engage with the Department of Defense. This includes contractors and other organizations in the defense contract supply chain, estimated to affect over 300,000 organizations. While CMMC may not fit the definition of a traditional regulatory framework, organizations seeking to work with the Department of Defense will need to demonstrate achievement at various maturity levels in the model. Interestingly, CMMC as defined is largely derivative of many other models, frameworks, and control sets, including a sizeable reliance on CERT-RMM, especially in providing the maturity structure for the model. Thus, while CMMC will be a requirement for some organizations, it is derived from both descriptive and prescriptive models, and implementation is more flexible so long as the intent of the practices in CMMC are implemented, verifiable, and evidentiary to support a specific achievement at a prescribed maturity level. Whew! CMMC is a perfect example of the symbiotic relationship between the body of models and frameworks we have at our disposal today. We suspect expect to see more models like CERT-RMM and CMMC in the future as the maturity model concepts take hold as a evolutionary driver for cybersecurity achievement, as we predicted back in 2002.

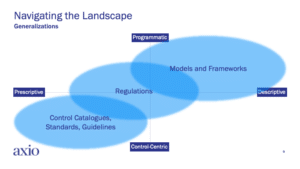

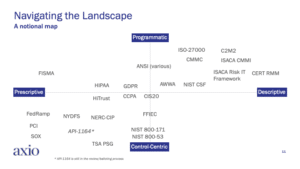

How to Generalize Frameworks

Over the years of model-building and model implementation, we observed that there are four factors that can easily be used to categorize the vast body of models and frameworks that organizations can select from. The above side demonstrates this “four-factor” view, broken into quadrants. The four factors of frameworks include descriptive vs. prescriptive and program vs. control (or better said, “what” vs. “how.”)

In the slide, the east-west axis moves from descriptive to prescriptive. Generally speaking, a descriptive framework provides more freedom in implementation. How your organization meets the stated objectives of the framework is your call. For example, if you use NIST CSF to define your program, you are free to use NIST 800-30 to implement the program at the practice level. In contrast, prescriptive frameworks tend to be more rules-based and highly specific. “How” you implement the objectives of a prescriptive framework might be decided for you in advance, particularly with certifications that might prescribe a certain process and set of measurable outcomes. Often, prescriptive frameworks are not chosen; rather, they are imposed on an organization either by membership in a group (i.e., an industry), to achieve certification, or to comply with regulations.

On the north-south axis, you’ll note the distinction between a programmatic versus a control-centric view. Using the four-factor view can help an organization to understand the primary motivation of a framework and the degree to which there is flexibility in implementation. Generically, models and frameworks tend to exist in the upper-right quadrant, control catalogs, standards, and guidelines in the lower-left quadrant, and regulations straddle the two.

Using the four factors, it’s easy to speculate where all of the common frameworks, models, control catalogs, and regulations “live” on the notional map. Many of us involved in the accompanying webinar spent a lot of time debating and trying to map these accurately. And, just as you will find as a consumer of these frameworks, being definitive about where they live on this map can be a tedious exercise that could change and evolve over time. Many frameworks don’t end up where they start out. For example, if they get broad distribution and use, they could become regulations and how they get implemented may become more prescriptive, especially if an industry is trying to correct perceived poor performance or behaviors.

If you have defined your framework imperatives and objectives, and are just starting to search for a suitable framework, the upper right quadrant may be the smartest place to look first.

How to Get Started with Frameworks (An Operations Guide)

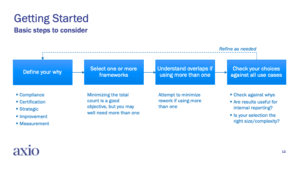

So, now that you are armed with more information about the various models and frameworks available, and their general characteristics, it’s time to decide which work best for you. After you’ve carefully considered your motivations and articulated your “why,” you can walk through the following steps to help you choose your ideal framework:

Adopting a model lends itself to the classic Plan-Do-Check-Act cycle. Here are some basic steps:

- Define Your Why: Decide on your most prominent imperative. Are you trying to improve your program or measure progress? Are there regulatory drivers which require you to prove compliance? Are you seeking certification to add value to your business?

- Select One or More Frameworks: Find the framework that solves your unique use case and can be expanded for future use cases. Use one framework if that fits, but consider that you might find yourself in a multi-model environment.

- Understand Overlaps If Using More than One: Figure out where the models intersect. Use the approach to “collect information once” and satisfy more than one model at a time. This can be done especially when using a control catalog that may be useful for implementing more than one framework or helping to satisfy compliance requirements.

- Check Your Choices Against All Use Cases: Validate that your choices cover all of your use cases today and in the future. Determine how much useful life you’ll get out of your initial choice.

- Repeat and Refine as Needed: Keep this going as long as needed.

Remember: Any model or framework you choose will require an organizational commitment to implement, manage, and evolve. Test drive a framework to ensure it fits your organizational objectives and compliance requirements. Refrain from choosing a framework that’s too complex or involved for your needs. For example, if you are just trying to get the basics in place, you might use NIST CSF. But, if you are already operating a program and want to evolve it, CMMC might add some much needed discipline and structure to mature your program.

Steps for Using Any Framework

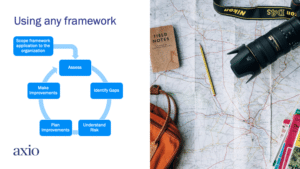

After you select a framework, keep in mind that this is just the beginning of the process. Adopting and implementing a framework is a series of interconnected steps that you may iterate. Consider the following progressive steps:

- Scope your framework application to the organization. You may decide to keep the initial adoption scaled to a department or unit, rather than the entire organization.

- Use the framework to determine how much of it you may already have accomplished.

- Identify gaps. Prioritize the gap areas in a way that you’ll get the most program improvement from small investments.

- Understand your risk. Determine what exposure your organization has as a result of the framework gaps. This may inform a re-evaluation of your gap prioritization.

- Plan improvements. Make a plan based on your priorities and follow it through.

- Make improvements.

- Repeat as needed, starting at the assess step. Determine if you have made progress and/or if conditions have changed such that your exposures require you to re-prioritize next steps.

About the author

Richard Caralli is a cybersecurity professional with nearly 40 years of experience in accounting, auditing, risk and resilience management, and process improvement. He is currently helping organizations implement and institutionalize GRC programs as a member of the consulting team at Seiso LLC, a solution-focused cybersecurity firm based in Pittsburgh. Prior to joining the Seiso team, Caralli held various senior level positions in information technology and cybersecurity in the oil and gas industry where he was responsible for developing and operating information and operational technology cybersecurity programs. Prior to returning to industry, Caralli was the Technical Director of CERT’s Risk and Resilience Directorate at Carnegie Mellon’s Software Engineering Institute where he was the lead architect of the CERT® Resilience Management Model (CERT-RMM), a process improvement-focused maturity model for managing operational resilience, much of which has been incorporated into various models including the Cybersecurity Maturity Model Certification (CMMC). Caralli’s research agenda was influential in developing and delivering coursework in information security to graduate and executive education students at Carnegie Mellon’s Heinz College. Prior to joining CERT in 2001, Caralli led accounting and IT audit teams in the banking, manufacturing and oil and gas industries.

—

If your organization wants to adopt a cybersecurity framework, Axio can help you chart a path forward. Axio offers free single-user assessments for frameworks including NIST CSF, C2M2, and more. Additionally, paid subscribers can receive reviews for CMMC, CIS 20, or custom setups. Check out the free tool here to learn more.